|

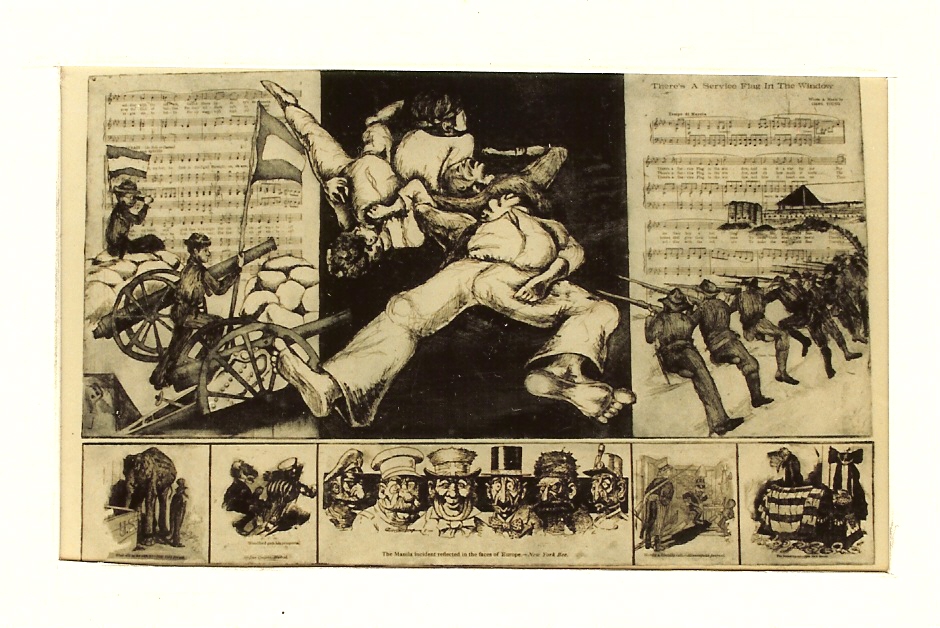

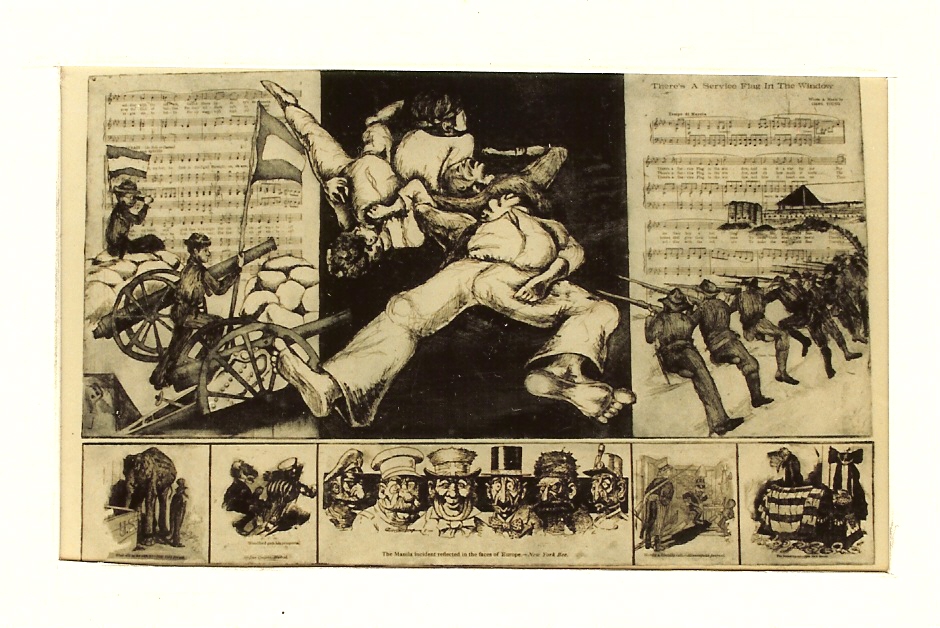

22''x30'' Etching - The song that appears in the background of this print was composed and written (music & words) by Colonel Young. The song was published in Xenia, Ohio in 1918. I did the drawings of the dead insurgents and American combat troops from Neely's photographs, "Fighting in the Philippines", published in 1889, which showed the human costs of war. The cartoons are from publications of original war cartoons of the period. Young was assigned to the Philippines in 1901 and he commanded troops at Samar, Blanca, Aurors, Daraga, Tobaca, Rosana and San Joaquin. From July 1901, to October 6, 1902, he participated in numerous engagements against the insurgents. The following are statements from a book by Marvine E. Fletcher The Negro Soldier and the United States Army 1891- 1917. Fletcher did this body of work as partial completion of a Ph.D. in History from the University of Wisconsin in 1968. “The Army had little trust in the Negroes ability to command and this became clear during the fighting of the Spanish-American War period. Shortly after the outbreak of war, Young, then at Wilberforce, asked permission to rejoin his regiment but instead of granting this, the Army assigned Young, with the rank of Major of Volunteers, to command the 9th Ohio Battalion, a Negro unit. While some Negroes at the time looked upon his assignment as a great victory, upon reflection it was seen as a device to keep Young out of combat. A few white civilians of Ohio objected to Young as an officer of a state unit, especially with the possibility that he might become a Colonel and they sent complaints to the War Department. Before anything could be done, the war came to an end and the regiment was disbanded; Major Young reverted to his regular army status but shortly thereafter the War Department, in the process of raising another volunteer army, this time to fight in the Philippines, at the suggestion of the President offered Young the senior captaincy in one of the two Negro regiments they planned. Young replied that he could take nothing less than a field grade commission in such a regiment because he felt that he could become a Captain in the regular service the following year anyway and more importantly he believed that his people would be upset by such a move, because they expected him to be a Colonel of that type of regiment." Fletcher concluded this statement with a statement by Young: "...the consideration of seven millions of a race is not to be ignored by me.” It must also be noted that even before the war with Spain in 1898, the Secretary of War, in a mistaken belief that black men were immune to tropical diseases, sent many black soldiers to countries with tropical climates.

While Young was serving valiantly in the Philippines, commanding segregated black troops, the Supreme Court decision of Plessy v. Ferguson - that declared that schools need not be integrated – had already been put in place six years earlier in 1896. So, “separate but equal” became the law of our land, and Jim Crow segregation laws became a national problem. That same year (1896), George Washington Carver, one of the most renowned of all African American scientists, was appointed director of agricultural research at Tuskegee Institute. At that time, George Washington Carver was the same age as Young because they were both born in 1864. At the turn-of-the-century, there was a World's Fair in Paris in 1900 - where the Untied States won several awards for the exhibition on black Americans. One of the primary organizers of the black American exhibits in the Exposition Universalle de 1900 in Paris was W.E.B. DuBois. Many of the photographs from this exhibit have been published by Library of Congress in an excellent book entitled: A Small Nation of People: W.E.B. Du Bois & African American Portraits of Progress with essays by David Levering Lewis & Deborah Willis. The book further illustrates similar advances make by African Americans at the turn-of-the-century that I have included in my "Young Photo Album " etchings and my "Legacy of Dignity" slide show on this website. These are the people who rose to prominence in every field even though many of their parents had been born during slavery. They are also the pictures of ordinary hardworking, industrious Ameicans who should never be forgotten. Ironically, at the same time at home - mostly in southern states, there were - between the years 1891 thru 1900 - well over a hundred lynchings yearly of black Americans totally 1,123 killings. These were hate crimes perpertrated by white racist lynch mobs who were known to have brutally murdered black Americans between the years 1891-1900. There was also a race riot in Wilmington, North Carolina in November 1898 where eight black Americans were killed. So, at the turn-of-the century in the 1900s, many black Americans were still being terrorized, brutalized, dehumanized, and traumatized. In spite of all of this unspeakable violence, Young kept a level head and commanded his men valiantly. In his book Military Moral of Nations and Races, Young wrote - only a few years later - these uplifting thoughts concerning his role as a soldier as it related to the principles upon which the United States was founded: "As nations become enlightened and the more democratic their rules, statesmen will give attention that the morale of the people is given such a trend that any war for national welfare will be readily aided by all classes, notwithstanding the sacrifices involved." Young fully understood that if the primary function of America’s involvement in any war were to be in defense of our national welfare, it would be supported by the majority of Americans, no matter what their economic background or race.

| |

-------- Copyright © 2007 by Joann Helene Sanneh All Rights Reserved --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------![]()